interview with régine debatty

Régine Debatty curator, critic and founder of we-make-money-not-art.com, a blog which has received numerous distinctions over the years, including two Webby awards and an honorary mention at the START Prize was interviewed recently about her upcoming class Art and Politics for Plants by artist and researcher WhiteFeather Hunter.

Your course, Art and Politics for Plants, immediately suggests, in the title, that humans are not at the centre of the equation. Do you see decentering the human as a critical position required for understanding not only our colonial/ capitalist impacts on the vegetal worlds but also for understanding the sensory capacities of plants? Do you think that by understanding their sensory capacities, we might understand their unique sentience and/or non-neuronal intelligence?

The human will actually be part of the discussion in several instances during the course. Mostly because the way humans (and particularly Western cultures) look at and exploit the planet has had such a massive impact on the vegetal world. It’s not always been for the best, of course.

Western cultures tend to see nature as a vast reservoir of services and resources to own and capitalise on. Plants, in particular, are often regarded as mere tools to exploit for food, medicine, fuel, industry and ornamental purposes. Over the years, however, this purely utilitarian viewpoint has revealed its calamitous consequences, displacing and marginalising communities, fostering inequality, threatening biodiversity and climate justice.

Time has come to co-evolve in a sympathetic and mutually beneficial way with the most important (in terms of biomass at least) inhabitants of this planet. We’ve got so many blindspots regarding other organisms. It’s particularly true when it comes to plants. We suffer from a kind of “plant blindness”. We think they are just part of the background.

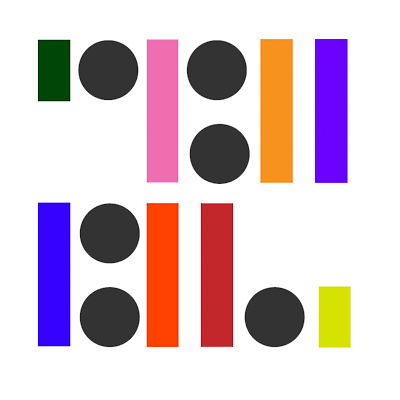

Stefano Mancuso, the director of the International Laboratory of Plant Neurobiology in Florence, opened his exhibition at the Broken Nature Triennale in Milan with this image. It says "What do you see?" The vast majority of visitors said "a tiger!" Very few mentioned the vegetation, even though it occupies almost the whole space.

Whenever I listen to a conference or podcast about the mass extinction of species, climate change, invasive species or anything related to the state of the planet and biodiversity, the discussions tend to focus on animals. It’s so much easier to relate to animals. We’re one of them after all.

One way to acknowledge the existence of plants and potentially feel more empathy towards them is to get to know them better and in particular to become more familiar with their extraordinary sensory capacities and their intelligence.

I found that art can play an important role both in fleshing out the socio-political facets of plants and in helping us understand their dimensions as sensitive, problem-solving living entities.

I expect some of the dialogue in your course will revolve around human diets. One of the arguments that I have heard made frequently by certain vegans is that animals are sentient and feeling but plants are not, which seems to me to be a problematic and limited worldview. I have to ask, do you tackle the politics of veganism or vegetarianism in your course? Is it from the perspective of not only unpacking colonial/ capitalist agendas but also unpacking the role of hierarchical speciation?

I wasn't planning to talk about human diets but your question is a very relevant and interesting one.

One of the arguments that vegans hear more and more these days is indeed that plants are intelligent too. This kind of remark is often used as a diversion, a way to eschew the issue of animal suffering. It puts the blame on vegans and suggests that they are not sensitive towards plants, therefore why should other people care about the animals they are eating? I know this is absolutely not your perspective but it pains me when some people suggest that just because you make the conscious decision of not contributing to the suffering of animals, you must automatically be cruel to plants and/or have no sympathy for your fellow human beings.

I don’t know any vegan who will deny that plants are alive and have developed many capabilities, smart defence mechanisms, awareness of their surrounding, sophisticated behaviour, memory and even have some forms of intelligence (for lack of a better word). I wouldn’t go too far, however. I’ve never heard any neuro botanist claim that plants can feel pain and suffering in the same way that seagulls or cats feel pain, for example.

As for sentience itself, it’s a tricky one I think. That’s probably why most vegans I know will be careful and insist on “suffering” rather than on sentience. As far as I know, there’s still some debate around the possibility of plants feeling pain. There’s no debate about animals feeling pain, though. Vegans will also often tell you that if you want to save plants, then a good start would be to avoid breeding those herbivores that have to be fed massive amounts of plants before they are killed to feed us.

Your question makes me realise that it might be interesting to have a discussion with participants about what botanist Francis Hallé calls the “radical alterity” of plants. They are so different from us that establishing parallels constitutes a perilous exercise. You can cut off more than half of a plant and it won’t die. You can’t do that with animals. The way their functions are distributed all over their body, the way they attract the world to them instead of moving to the world is very different from what we know.

That’s what I find infinitely fascinating. To fully understand and learn from plants, it is important that we appreciate them for what they are. If we keep comparing them with animals we might miss their true value and specificities.

I love that you'll be bringing in the concepts of symbiosis and holobiont existence. Do you think that by challenging our notions of speciation and perhaps allowing for some kinds of interspecies identities (such as 'human' as a microbial, mycobial, insectoid/parasite, etc. superorganism), we might unravel the capitalist agenda by moving towards the dissolution of individuality?

The answer to that one is easy: no. I sincerely wish I could say yes but I’m too pessimistic for that. Just as I was reading your question, my boyfriend sent me this link on Skype. It says that despite the protests from WWF and from citizens, the mayor of the city of Vieste in Italy has cut 52 healthy pines.

The trees had been there for 35 years but he wanted to make space for a parking lot. When asked to explain his motivation, the man answered “The place of a tree is in the forest”. At first, all sorts of invectives came to my mind but, in a sense, he is right. For a tree, it must be so much more pleasant to be in a forest than to be used as decoration in urban settings. Or as a support for the mental well-being of city-dwellers.

To come back to your question, I really wish we would take better care of the infinitely small forms of life we depend upon but we can’t even seem to be able to care for the big (and in some cases the most charismatic) beings that surround us, that we admire, that we depend upon and that are clearly threatened. There has been a lot of press coverage about the microbiome and many people are certainly more interested in this invisible life than ever but mostly because we -and when I say we I mean people in the "West"- know it plays a major part in keeping us, human individuals, healthy physically and mentally.

In light of the setbacks, shortcomings and incapacities of individual humans and humanity as a group (especially Western society) to move effectively towards a more equitable, sustainable future, what do you envision as artistic action(s) that can address or minimize the undesirable impacts of our existence on the planet? Can you give us a sneak peak into some of the activities you'll highlight in your course?

I tend to be both enthusiastic and cynical when it comes to the kind of impact(s) that artistic actions can have on the way society is moving ahead. I think the difference lies in the way the art is deployed and actually meets a public that is not limited to the usual museum audience.

If you encounter art that engages hands-on with social, economic, ecological or political issues, you can discover and learn a lot, you can be moved and inspired. It’s the eye-opening side of art.

An example of that would be the collaboration between botanist Stefano Mancuso and artist Carsten Höller (who happens to also hold a doctorate in agricultural science.) Back in 2018, they worked together on The Florence Experiment, organising all sorts of entertaining activities for humans at Palazzo Strozzi and analysing how the interaction between plants and humans affect plants. It’s usually the other way round: most experiments look at the effect that plants have on our well-being.

The results of the experiment were humbling. It turns out that plants don’t like to hang around with us as much as we’d like to think. We need them more than they need us. But you knew that already.

Another example of art and science projects I might discuss during the course is Agnes Meyer-Brandis’s Office for Tree Migration. The research project, developed in cooperation with researchers from the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the University in Groningen (NL), opens up discussions about how much scientists should assist trees trying to “escape” global warming and about the kind of impact this displacement might have on ecosystems further North.

As I mentioned earlier, the political dimensions of plants will play a big role in the course. In Foragers, for example, artist Jumana Manna reveals the daily acts of defiance performed by Palestinians when foraging wild plants for food and medicine.

Over the past few decades, the state of Israel has imposed regulations which, under the claim of protecting plants, make the act of picking thyme and other plants essential to Palestinian cuisine punishable by fines or even prison. It’s the kind of works I’d like to highlight in the context of a discussion around green colonialism.

There are also works that, in their own modest ways, simply make the world a more pleasant place to live in. I’m thinking of Alan Sonfist’s famous Time Landscape in Manhattan. I'm also thinking of artist and anthropologist Leone Contini whose performances and installations bring together migrant communities who often travel to Europe with seeds in their pocket in order to grow a piece of home vegetation in the new country.

One of the most interesting lessons that emerged from Contini’s work is that these freshly arrived farmers have to revise their know-how and adapt it to the local climate and soil. They become pioneers of “displaced” and confused agriculture. Their resourcefulness and the knowledge they accumulate with each experiment might even turn useful to Italian farmers. As Contini notes, traditional local farming in Italy is challenged by an environment in constant mutation: unseasonable weather, soil erosion and other disruptions have turned local farmers into migrants onto their own land. His work thus opens up a fertile space for intercultural dialogue.

Then there are works that have more immediately tangible impacts. With Plantón Movil, Lucia Monge literally takes people and plants to the street to peacefully protest together against the lack of parks and other green areas. She had people and plants march together in various cities across the world and sometimes these amusing performances actually lead to the creation of green spaces.

What I love about the works of Leone Contini and Lucia Monge is that these are interventions that are not enclosed inside the pristine walls of a gallery or museum. Their works find their public in public parks, in greenhouses, in the streets, etc. That’s the best way to generate fruitful debates with the rest of society.

One thing I'd like to add is that no matter how pessimistic I claim to be, I can be incredibly uplifted by the work of activists, too. Take geographer Radjawali Irendra for example. In 2014, he founded Akademi Drone Indonesia (ADI), an organisation dedicated to research, education and policy surrounding unmanned vehicles for terrestrial and aquatic research and an advocacy interested in environmental issues. Indigenous communities and poor people whose land rights are threatened use his ADI’s drones to collect detailed spatial data, create their own aerial imagery and challenge official narratives.

These are the kinds of works my course aims to bring forward. To learn more about plants and art of course but also to highlight the efforts of artists, designers, activists and ordinary citizens who, each in their own way, attempt to address the most toxic impacts of our actions on the planet and on its inhabitants in all their forms.

Art and Politics for Plants will run online from 01. February every Monday from 7-9pm CET until until 01. March. There are only a few spots left. To reserve yours, visit: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/art-politics-for-plants-tickets-133592249013